School of Medicine faculty, staff stayed on the job for COVID-19 crisis

Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers have been praised for treating an influx of sick patients and for keeping hospitals running as the crisis unfolded.

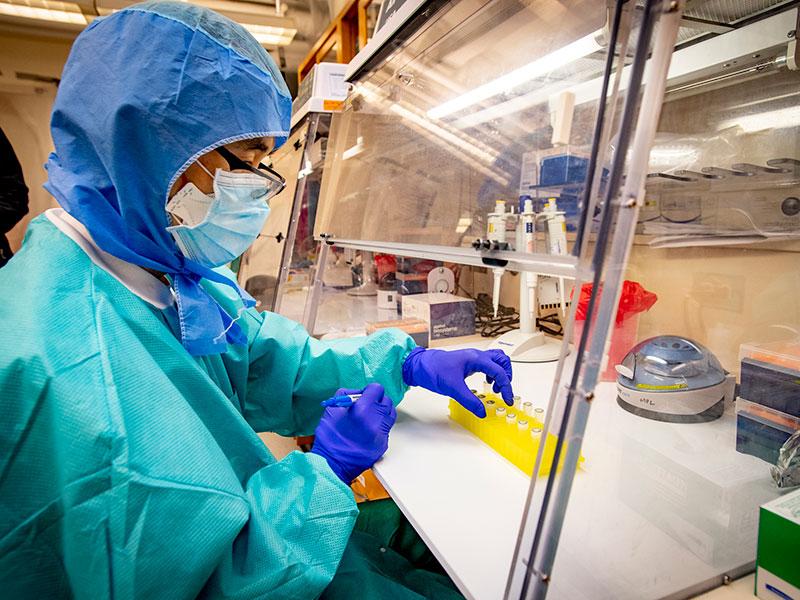

At Tulane School of Medicine, the majority of faculty members, staff, residents and researchers, as well as some medical students, never left campus. They kept working through the early days of the shutdown, following an evolving set of guidelines on safe practices to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“Our physicians, scientists and staff have always worked with the goal of benefiting humanity. During this pandemic, the tireless dedication and creativity employed by the entire School of Medicine community to achieve our missions of discovery, learning and healing have been simply incredible to witness firsthand,” said Lee Hamm, MD, senior vice president and dean of the School of Medicine.

Erin E. Boh, MD, PhD, the Joseph Chastain Endowed Chair of Clinical Dermatology, said the Department of Dermatology faculty, residents and staff helped out their colleagues, with some residents working on the wards and faculty helping conduct drive-through testing.

“All of us, throughout the whole big wave of epidemic, did some part. People would take appropriate precautions, but they still worked when they could, and if they needed to, they worked every day,” she said, noting that other departments and hospital employees did the same.

“We brought our Purell with us everywhere we went,” she added.

In the early days of the shutdown, Mimi Sammarco, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Surgery, and her research staff honored the university’s request to minimize on-campus staff. But their research on promoting limb regeneration and salvaging tissue, muscle and bone after traumatic injury could not drop off indefinitely.

“We decided we were going to come back because the experiments really required it. We followed Tulane’s rules, which I think were excellent recommendations,” Sammarco said. She nonetheless offered her team members the option to stay home if they felt uncomfortable, but they decided to return eventually with appropriate COVID-19 precautions, even when it was difficult to stand 6 feet apart in a tight space.

Those precautions gave way to adjusting to everyday disruptions caused by COVID-19, such as when the physically distanced cafeteria lunch line wound down the hall, she added.

For Geraldine Ménard, MD, associate professor of Medicine and chief of the Section of General Internal Medicine and Geriatrics, the COVID-19 precautions that were new to so many people are part of her everyday experience.

“For me, it’s an occupational job hazard, frankly. I treat patients that have tuberculosis, where I have to put on PPE. When we have patients that have influenza, or suspected influenza, we put on the face mask.”

“We’re very fortunate —we did not have a single faculty member [in the Department of Medicine], that we are aware of, that was diagnosed with COVID. People were very attentive to the donning of the PPE. And following all the restrictions.”

Ménard said her experience during Hurricane Katrina helped her manage the unfolding situation with hospital faculty. Then, as now, constant communication was important on both ends. Sometimes she updated her faculty three times a day to keep them apprised of the latest developments.

But the basic COVID-19 advice is still solid: “I think that's probably the biggest piece: People need to wash their hands. They need to wear a mask. They should wear a mask when they go out of their house,” she advised.